View of a retinal at the back of a human eye

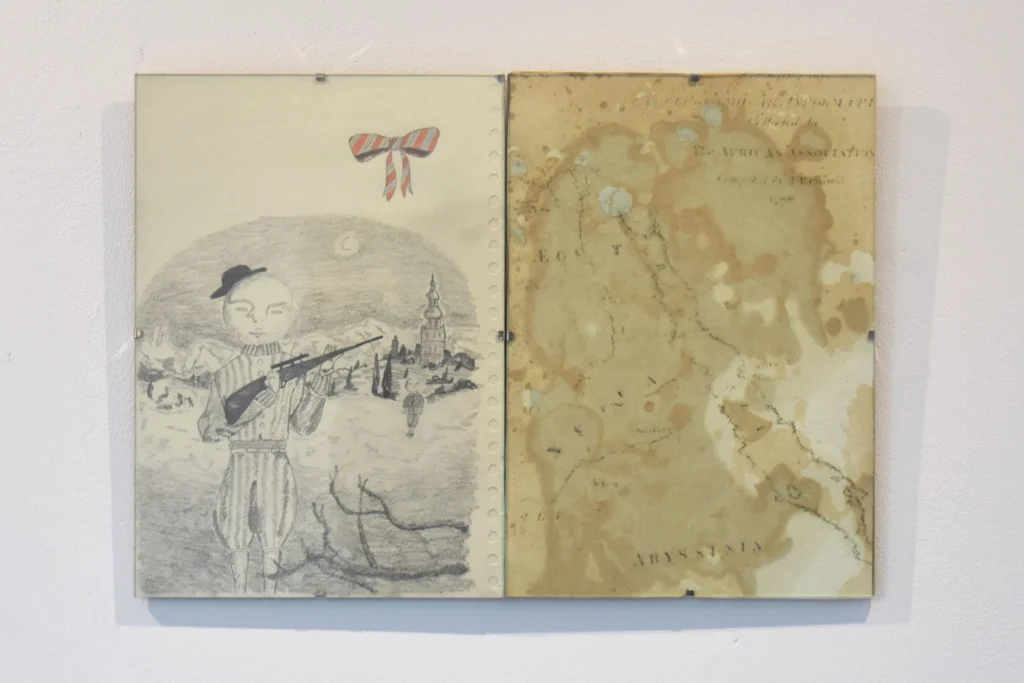

How many near identical images exist? Many landmarks, many views, but there are categories that are more transcendent than cliche: Photos of mothers holding a baby, portraits of a loved one, children on a family holiday, school photos, yearbook portraits, wedding pictures. I can imagine all of these within my own biography and have the feeling of seeing these pictures before even though I am likely just imagining an amalgamation of other peoples photos and lives embedded within the aesthetic of personal archives.

We can extrapolate this to a political level as well. Fighters with guns, taking a monument, inauguration, revolution, broken cities, wounded children, graves, trials, government buildings, reconstruction. We all know these photographs but are likely unable to remember the specific context that each image is extracted from. For some, sure it’s obvious, the Soviets raising a flag atop the Reichstag, a young girl burned by napalm, a drowned boy on the shores of Turkey. I struggle to work out if I ever actually saw Kenndy’s blood across the back of a convertible. Times and wars blur together and somehow history is created.

The eyes of photographers become trained to capture what they see before hence we get more baby photos and men with guns. Now our memories have corners, and places have edges determined inside the shutter before the walls are even built.

But what if images were more than just artifacts of reproductions? Rather than seeing them as papers or screens we can take the term ‘image’ to mean a series of impressions imprinted on our bodies and consciousnesses. Some still remain hidden and some are bright and bold and electric but they all bleed into each other as action and language combs through the dregs of our memories.

This concept of an image inherently mixes received narrative (often strongly sculpted by the powers that be) and unsorted thoughts, feelings, smells, tastes and visual fragments. We can try to create some myth of chronology, inserting ourselves crudely into ‘the current moment’ of so called history but the reality is that these chains of events can never be set. They are just stories we tell each other and then forget as we drift off to sleep. Occasionally one image will be dredged up and disrupt the determined flow of political time, rewriting narrative and dirtying the waters. In this sense we see great radical potential for this working concept of images; it takes the historical material of bodies and impressions as something immutable and imminent. And in a way can testify that something committed 500 years ago is just as current as something occuring now. It demands that we should always be at points of reckoning, alert to our surroundings and the structures of exploitation we find ourselves within.

It is a concept that can describe how we pour ourselves into politics and politics pours itself into us. It is one that lets us be whimsical while acknowledging the brutal stripping of innocence so many of us become confronted with when we first learn what people are capable of. Most importantly it insists on an ecology of information where everything is alive and capable of change. It strips us of the myth of the individual and resists those who claim they can conquer truth. Text by Will Hilless